Brooke Laird's Portfolio

Hi there! My name is Brooke and I am a senior Geography and Environmental Studies major at Middlebury College. I am passionate about using GIS, remote sensing techniques, and cartographic design to expand on studies of environmental justice, recreational access, climate change adaptation, and landcover change. On this page you will find my work from various courses, independent study, and research positions.

Addressing Error and Uncertainty in GIScience

This week in our reading of Geographic Information Systems and Science by Longley et al. we explored the topic of uncertainty in spatial/geographic research. Engaging in discussions surrounding uncertainty is a necessary first step that all geographers must take to develop a meaningful framework for how to view their work, and the geographic work that they are exposed to. I appreciate the tone that Longley et al. set in this article, as they view uncertainty as a result of complexity and a natural phenomena that must be addressed, instead of an error that must be avoided, or never addressed in the first place. By beginning to accept uncertainty as a natural occurrence in spatial research, our work as geographers will be more meaningful.

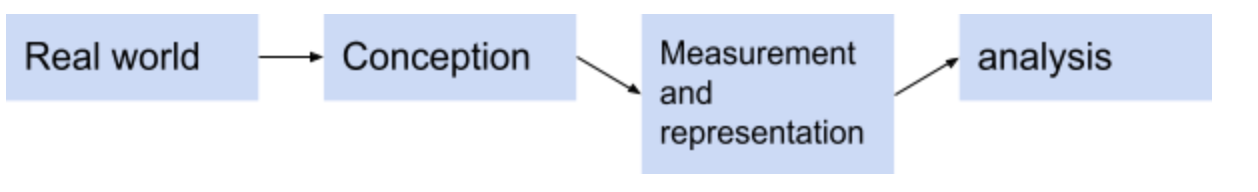

In figure 6.1 of the chapter, Longley et al. illustrate the linked pathways and filers that lead to the build up of uncertainty. This pathway addresses the uncertainty in research as you move from the real world to analysis, while creating conceptions of this real world, and taking steps to measure and represent the processes at hand.

This was an important diagram for me, because while I have thought about the uncertainty that stems from problems in measurement, representation, and analysis, I rarely think that my conceptions of the real world could lead to uncertainty in my geographic work. However, there are various instances where my conceptions of the real world may have created a greater degree of uncertainty in my produced work, such as the process of ground truthing classification points based on my perception of how land cover should be classified, or creating buffers around a central business district that is defined by my consideration of what the CBD is.

In order to address complexity and uncertainty in geographic work, there are a variety of steps that can be taken to improve the research process. Longley et al. mention “fuzzy sets” as one way of working with uncertainty, which allows classification categories to be less rigid, and more open for variation. Additionally, while GIS work can be particularly useful because of the easy process of data set merging and overlaying, this step should be done with a critical eye for potential error. Oftentimes datasets may seem similar, but a small amount of geographic unevenness could contribute to flaws in the representation and analysis.

Most importantly, geographers can deal with uncertainty by adopting a “spirit of humility rather than conviction” in regards to their produced work (pg 152). I think that the growing popularity of open source GIS can help contribute to this spirit, as open source work leads to more collaboration, documentation of changes and steps, and clear documentation of data. If research is being conducted with the hopes of getting published in a journal, and the error margin must be extremely low, then it may appear more attractive for geographers to shift hypothesis or data results. But Longely et al. emphasize that it is “better to take a positive approach by learning what one can about uncertainty, than to pretend that it does not exist.”

Readings for the Week: Longley, P. A., M. F. Goodchild, D. J. Maguire, and D. W. Rhind. 2008. Geographical information systems and science 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley.